Explore one of Islam´s most beautiful City

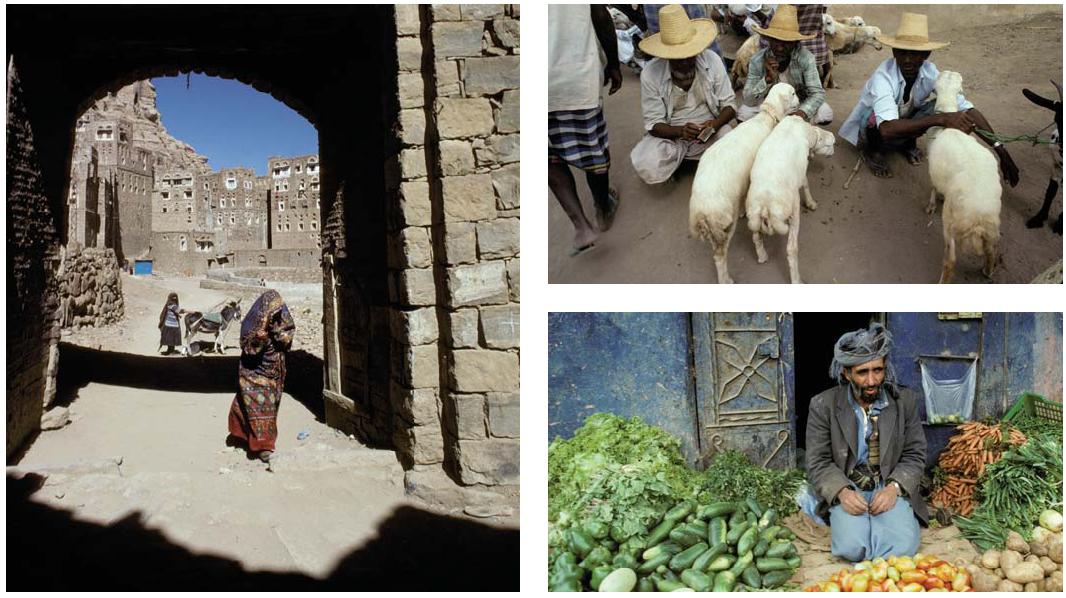

Ali was insistent. “My friend, look here, nowhere else. My spices are the best! ” The wily merchant gestured towards his wares. “ I have everything you need for chicken, for lamb… everything for the pot,” he continued, his English impeccable. Trawling for goods through Isfahan’s sprawlingsixteenth-century Bazar-é Bozorg, or great bazaar, is a beguiling experience. This is one of the oldest bazaars in Iran, a mesmerising maze of brick passageways and domed galleries, chaotic and compelling in equal measure. I had made my way to the sprawling market from the city’s Armenian quarter, located on the south bank of the River Zayandeh.

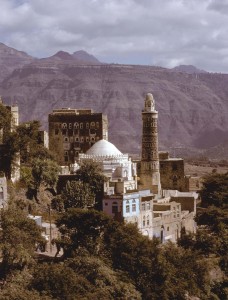

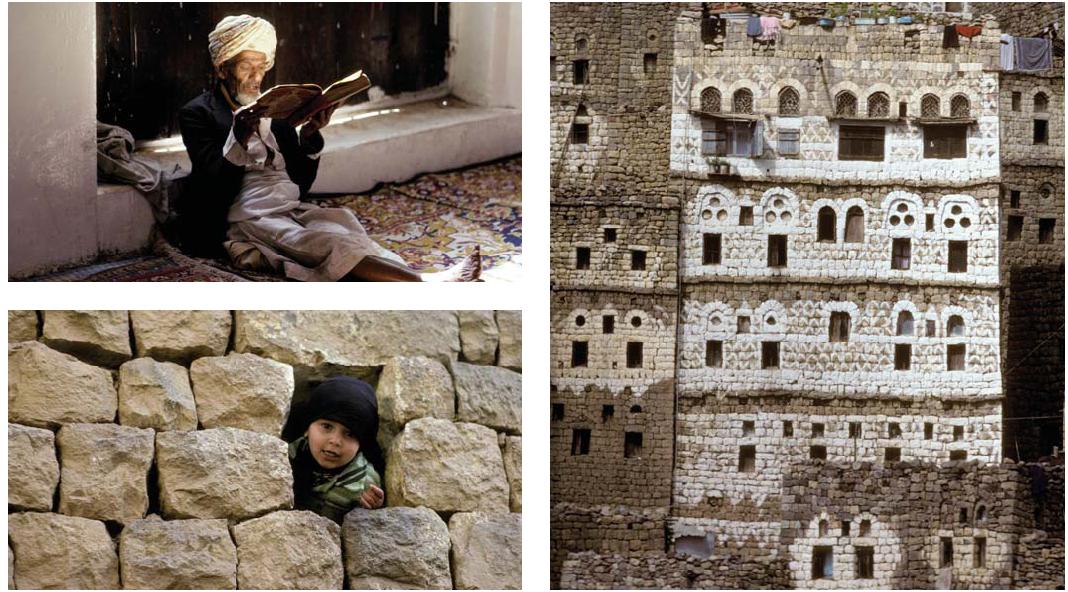

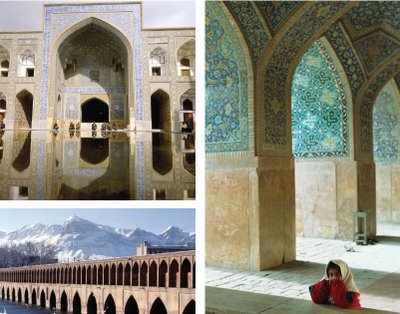

My exploration of this predominantly Christian enclave was supposed to have been fleeting at best, but the macabre frescoes adorning the Church of Bethlehem were deserving of a more considered foray. The images depict in extraordinary deta i the tortures of various hapless saints – a barbaric, bloody canvas totally at odds with the peaceful air this otherwise plain building exudes. A more uplifting exercise was the amble across the elegant Si-o-Seh Bridge, named after its 33 arches. Its span reminded me of a long, narrow finger pointing the way into the heart of ancient Isfahan and the splendours therein. The bridge (one of 11 over the Zayandeh) is particularly attractive at night when, illuminated, its teahouses attract custom like moths to a shining lamp. Ali’s stall was the colour of autumn, a vivid palette of amber, sienna and terracotta. Generous heaps of ground cinnamon, barberry and turmeric spilled over the rims of huge copper bowls. Pinned to the walls were sachets of delicate, honey-coloured saffron hand-picked near Mashad, Iran’s holiest city. Plump, juicy figs har vested in the south of the country glistened under the warm tungsten glow of lamplight, which, in turn, cast an inky half-shadow across Ali’s robust frame. The bittersweet aroma was intoxicating, the tangy fragrance hanging in the air like an unfinished sentence. I took a deep breath. These were the flavours of the Safavids and the Third Persian Empire, when Isfahan was the nation’s fine capital, and trade with the Orient blossomed. Ali scooped up a mug of pistachio nuts and tumbled them into my cupped hands before selecting a tall jar filled to the brim with colourful layers of mixed condiments. “A spice for every day of the week,” he quipped with a grin. Our transaction over, I thanked the mercurial bazaari and said farewell. “Khahesh mikonam,” he boomed, shaking my hand. “You are welcome.” To stand in the middle of Imam KhomeiniSquare, Isfahan’s magnificent central plaza, is to gaze upon some of the greatest monuments in th e Islamic world. Flanking this quadrangularlandmark is the beautiful Imam Mosque, the smaller though no less elegant Sheikh LotfollahMosque and the curious six-storey Ali Qapu Palace. Captivated, I was particularly drawn tothe Imam Mosque, a masterpiece of seventeenth- century Persian architecture.

The building is a visual feast of intricate mosaic calligraphy and rich floral motifs set within a wash of turquoise-blue tile work. The grace ofthe craftsmanship is such that it’s no wonder Robert Byron, writing of Isfahan’s mosques in The Road to Oxiana, remarked that he had ‘never encountered splendour of this kind before’. Neither had I. I spent over an hour in the majestic confines of this Safavid treasure and tried to reconcile all the negative comments that I’d heard about Iran in the West, with what stood before me – but couldn’t. Suffice it to say it’s very unwise to pass judgement on a place and its people until you’ve been there and met them. Finally, I left the complex and headed for the the Qeysarieh Tea Shop at far end of the square.A favourite meeting point for travellers, the tea shop is also popular with young Isfahanis eager to chat with foreigners. I’d taken a place at one of the tables when two Iranian women, both clad in long-sleeved coats, sat near me. I guessed the pair to be in their early twenties. Both wore headscarves high over their foreheads to expose silky locks of raven hair. Thin black eyeliner and a hint of lipstick completed the picture. This wasn’t the first time I’d noticed the subtle bending of the rules governing the hejab – the strict dress code adhered to by women across the land. But on this occasion I dwelt more thoughtfully on the fac t that many people in this country – male and female alike – are yearning for sweeping legal and social reform. Eventually, after a couple of furtive glances one of the women leaned forward. “Do you speak English?” she said. “Can we ask you something?” I straightened up. “Of course you can.” “Where are you from?” I told them. “Are you married?” The question caught me totally off guard. For a moment I was lost for words. “Erm, no,” I spluttered. “Why not?” “Well I… I don’t know,” I replied, shrugging helplessly. My clumsy answer elicited a burst of laughter from both before a quick deliberation in whispered Farsi. “And are you enjoying your stay in Isfahan?” the other inquired. “Yes, absolutely!” In fact it was “an educa tion,” I added, finding my feet.

I described my visit as a wholly enlightening experience, while the two listened attentively, nodding occasionally as I rambled on. “But what is it like living in the West?” began the interjections. “Is it expensive? Have you been to America? We would like to travel too….” Thus our conversation continued, a curious exchange of guarded opinion and wishful thinking, interrupted only by the arrival of a pot of tea, a bowl of crunchy sugar cubes and three glasses. Soon, the pale afternoon light began yielding to the lilac shade of encroaching nightfall. Pausing, I stole a glance back across ImamKhomeini Square, its regal outline now bathed in a floodlit wash. Was this the view that prompted the well-known sixteenth-century Iranian proverb Isfahan nesf-é jahan – ‘Isfahan is half the world’? I convinced myself that it was.