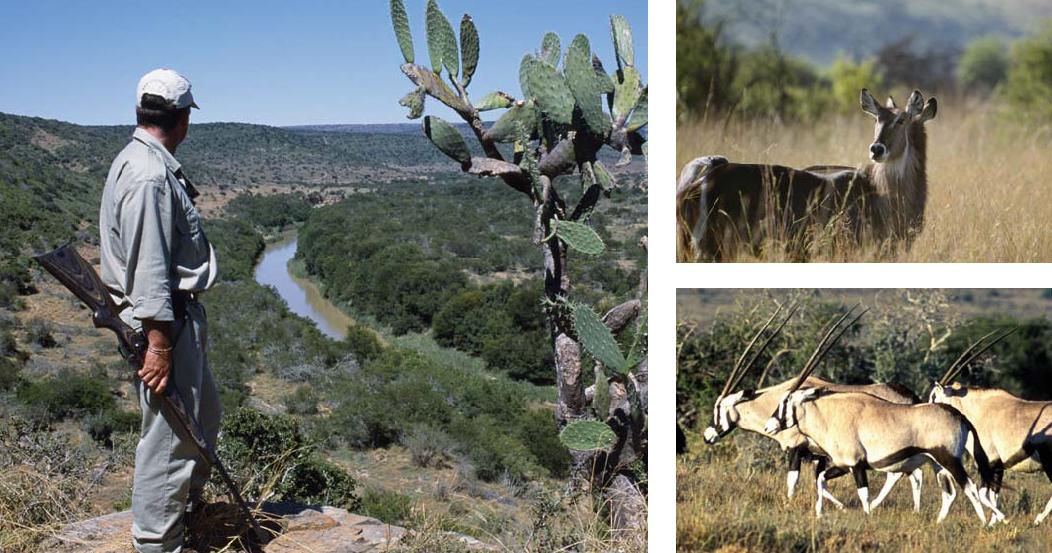

Looking out over the Kwandwe, I had a vision of South Africa’s Eastern Cape before the early settlers changed the landscape. Herds of noble gemsbok sent up clouds of dust as they galloped away across the veldt. Lines of black wildebeest traipsed past us like grumpy old men, their long faces set with their trademark lugubrious expressions. Ostriches flounced about, ruffling their skirts like can-can girls. A cheetah sat with perfect poise in the shade of a small acacia, surveying the Fish River Valley below. There is nothing like experiencing nature up close and personal. Seeing wild animals so close is a scary but exciting experience. Seeing these wild animals so close, will stir up fear, excitement and awe. It is like nothing you can ever describe or even begin to imagine until you try it for yourself. Our guide, Andrew Mortimer, led the way to the water’s edge. Among the mass of spoor, he pointed out the pugmarks of lion, the long cloven hoof prints of giraffe and the broader heavier imprint of Cape buffalo. A rustling amongst the grass made us look up. A leopard tortoise slowly lumbered up to within a few metres of us before retreating into its shell. Driving on through the rolling country, Andrew located a group of white rhino. We sipped our sundowners and listened to his tale of how the rhinoceros got its horn, as we waited for the sun to go down. Night-time game drives are often over-rated, but our journey back to the lodge was enchanting. Our African tracker, Solomon, picked out a Disney-esque cast of new characters with the spotlight. Spring hares bounced away like mini kangaroos; nightjars fluttered up in front of us like angels from the warm dusty track; aardwolf slunk through the undergrowth and the chance of spotting an aardvark, a form of primeval ant-eater with enormous ears and a comically long snout, had us on the edge of our seats.

Looking out over the Kwandwe, I had a vision of South Africa’s Eastern Cape before the early settlers changed the landscape. Herds of noble gemsbok sent up clouds of dust as they galloped away across the veldt. Lines of black wildebeest traipsed past us like grumpy old men, their long faces set with their trademark lugubrious expressions. Ostriches flounced about, ruffling their skirts like can-can girls. A cheetah sat with perfect poise in the shade of a small acacia, surveying the Fish River Valley below. There is nothing like experiencing nature up close and personal. Seeing wild animals so close is a scary but exciting experience. Seeing these wild animals so close, will stir up fear, excitement and awe. It is like nothing you can ever describe or even begin to imagine until you try it for yourself. Our guide, Andrew Mortimer, led the way to the water’s edge. Among the mass of spoor, he pointed out the pugmarks of lion, the long cloven hoof prints of giraffe and the broader heavier imprint of Cape buffalo. A rustling amongst the grass made us look up. A leopard tortoise slowly lumbered up to within a few metres of us before retreating into its shell. Driving on through the rolling country, Andrew located a group of white rhino. We sipped our sundowners and listened to his tale of how the rhinoceros got its horn, as we waited for the sun to go down. Night-time game drives are often over-rated, but our journey back to the lodge was enchanting. Our African tracker, Solomon, picked out a Disney-esque cast of new characters with the spotlight. Spring hares bounced away like mini kangaroos; nightjars fluttered up in front of us like angels from the warm dusty track; aardwolf slunk through the undergrowth and the chance of spotting an aardvark, a form of primeval ant-eater with enormous ears and a comically long snout, had us on the edge of our seats.

Andrew’s piece de resistance was to wind up a cheeky genet cat by imitating the plaintive squeaking of a mouse, which drew the genet right up to the side of our vehicle Next day, Andrew asked if I would like to watch the release of the last animals to be translocated to Kwandwe. From our safe vantage point on the roof of the huge container truck we looked on as the translocation team raised the tail-gate and five hippopotami tripped down the ramp, paused to sniff the air of freedom and charged along the narrow chute that channelled them towards the dam before launching themselves into the water like unstoppable submarines. Standing beside me was Angus Sholto-Douglas, Kwandwe’s reserve manager. For Angus this moment was the final realisation of a dream that began as a chance encounter four years previously. He and his wife Tracy were head ranger and camp manager of King’s Pool Camp in Botswana when Erica Stewart, a high-flying marketing consultant, and her partner Carl de Santis, a vitamins billionaire, came to stay. For Carl it was to prove an expensive safari. He had never been to Africa before, but instantly fell prey to the spell of the bush. The two couples struck up a rapport. Over long dinners, talk became dreams, dreams became plans and, by the time that Carl and Erica left, they had commissioned Angus and Tracy to go and find them a suitable piece of land somewhere in Africa to purchase and establish their own game reserve. Eight months later, having looked at land in Namibia, Botswana and further north in South Africa, Angus settled on the Eastern Cape. The absence of tsetse fly and malarial mosquitoes had made this land perfect ranching country. Wildlife paid the price, falling prey to the settlers’ guns and fences. Gradually the land had been taken over for agriculture and wildlife was driven away. Angus proposed to reverse history by expelling the farm livestock and reintroducing wild game. Following Angus’s recommendation, Erica and Carl flew to South Africa, a country neither had visited before, and bought Kranzdrift, a 5,500- hectare ostrich and goat farm. Kwandwe was born. With ostrich farming in decline, other parcels of nearby land came on the market until they had acquired a total of 16,000 hectares. Rehabilitating the land has been a prodigious task.

Over 2,000 kilometres of paddock fencing had to be ripped up, water towers, windmills, metal pipelines, troughs and other agricultural refuse removed. The transformation has been miraculous. Before the first of the wild animals could be released, 110 kilometres of game fence had to be erected around Kwandwe’s perimeter. Two by two they came off the translocation team’s lorry: the plains game first – wildebeest, zebras, springbok, giraffe and blesbok; then black rhino, white rhino and disease-free buffalo. A year later the prestige species were re-introduced: elephant, lion and cheetah (leopard had somehow survived the settlers). Now we were watching the arrival of the last of a staggering 7,000 introduced animals, the hippos. Buying and selling wild species in a coordinated market place, introducing animals to fenced areas too small to function as natural ecosystems, controlling game stocks and at times even grooming habitat to facilitate game viewing, can appear invasive. I have visited many private reserves in South Africa that feel more like a wildlife theme park than a genuine natural environment. Kwandwe has not fallen into that trap. The land has reverted to near-pristine wilderness in a remarkably short time, the perimeter fence is unobtrusive and the animals appear comfortably settled in their new range. The limited area of the reserve may not allow for natural migration patterns, but if Angus’s long-term vision is realised and more land packages are added, Kwandwe may become the kernel of a rehabilitated Eastern Cape ecosystem.

Hotels and Resorts in South Africa

Kwandwe Private Game Reserve in the Eastern Cape has three exclusive safari lodges, each offering great Big Five viewing. Kwandwe main lodge is set along the banks of the Great Fish River and has nine suites with private plunge pools and thatched game viewing decks. Uplands Homestead is a restored farmhouse of three en suite bedrooms with private terraces. Kwandwe Ecca Lodge has six suites.

Satara Restcamp in the centre of Kruger National Park recalls the colonial past in its architecture and offers the best chance of spotting lion, leopard and cheetah.

Phinda Forest Lodge is all about luxurious and clean modern living in the heart of the Kwa-Zulu Natal bush. It comprises 16 spacious, glass-encased bungalows built on stilts in a vast private game reserve, together with viewing decks that afford panoramic views across the game-filled plains. It’s also just 30km from the white beaches of the Indian Ocean.

Hluhluwe River Lodge contains 12 exclusive thatched chalets, dotted around a pretty indigenous garden,

each with its own viewing deck over the Hluhluwe River floodplain and False Bay.

Lebombo Lodge is another luxurious Kruger safari haven, built on steep terrain in a picturesque corner of the park. The individual suites have floor-toceiling windows, ensuring the rooms are full of light and dramatic views. Meals are served in a traditional reedenclosed boma around a log fire.

Top destinations in South Africa

- Kruger National Park One of Africa’s best game parks, and one of the few where you can drive yourself around. So take to the back roads of this reserve the size of Wales, and enjoy fabulous wildlife and excellent accommodation – from campsites to luxurious cottages.

- Stellenbosch Relax and unwind in the heart of South Africa’s wine industry, home to over a hundred cellars, most of which are open to the public.

- Capte Town Ride the cable car to the top of Table Mountain for views across this beautiful seaside city. Then wander to the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront for shops, museums, aquaria and street entertainments.

- Garden Route Journey along the beautiful southern coast, a wonderful area for beaches, birdwatching,

dolphins and whales. - Kwandwe A new and luxurious private game reserve, as described in our main feature.