Peshawar: It was November and cold winds were beginning to sweep down from the mountains. A photographer and I were heading up to the valleys of the legendary pagan Kalash tribes,near Chitral. I needed a chaddar, one of the rough woollen shawls that Pathan men wear around their shoulders and sometimes round their heads.These double as blankets, pillows, tarpaulins and even as swaddling for babies. I wanted one partly for the cold nights in the valleys,but also to make me less conspicuous as a foreigner on our drive north through Pakistan’s rugged tribal areas. This meant a trip into Peshawar’s Old City, from our guesthouse on Railway Road. The modern bazaars in the University and Cantonment areas of Peshawar are fine for buying batteries, sim cards or books,but for traditional Pathan clothing you have to enter the strange medieval world of the Old City. We went at night.Peshawar has long been in the grip of what the local papers call ‘the late night shopping craze’,which they blame for shortages in electricity.

Peshawar: It was November and cold winds were beginning to sweep down from the mountains. A photographer and I were heading up to the valleys of the legendary pagan Kalash tribes,near Chitral. I needed a chaddar, one of the rough woollen shawls that Pathan men wear around their shoulders and sometimes round their heads.These double as blankets, pillows, tarpaulins and even as swaddling for babies. I wanted one partly for the cold nights in the valleys,but also to make me less conspicuous as a foreigner on our drive north through Pakistan’s rugged tribal areas. This meant a trip into Peshawar’s Old City, from our guesthouse on Railway Road. The modern bazaars in the University and Cantonment areas of Peshawar are fine for buying batteries, sim cards or books,but for traditional Pathan clothing you have to enter the strange medieval world of the Old City. We went at night.Peshawar has long been in the grip of what the local papers call ‘the late night shopping craze’,which they blame for shortages in electricity.

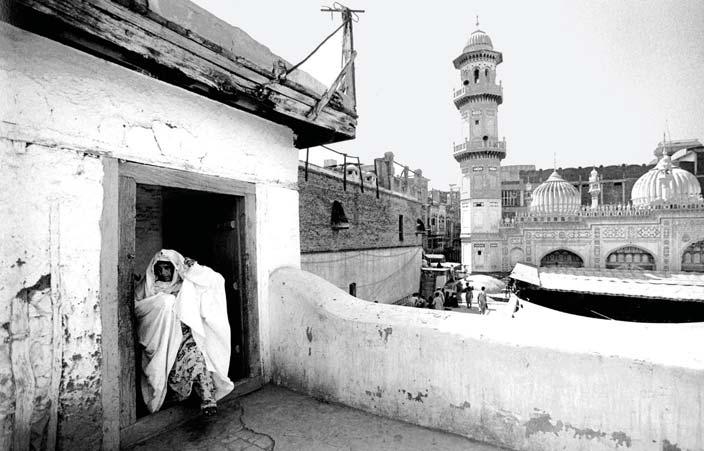

The racket of poorly maintained motorcycle engines and vehicle horns is incessant. Unlike the ordinary shopping precincts of the city,here almost everyone is bearded, and no one wears Western clothes. Women,a rarity in the daytime – and all but invisible then beneath burqas – are completely absent by nightfall. Peshawar is not only the capital of the North-West Frontier Province, it is the headquarters of Pakistan’s pro-Taliban fundamentalist party, the mma,and place where ultra-conservative Islam and harshly ascetic tribal tradition sit uneasily with the modern world of cinemas, tourism, stores selling music CDs,and even Chinese restaurants where unveiled women serve male customers. All of the latter have provoked demonstrations and bombs in recent years. In the Old City, the bristling masculinity of the Pathans colours every encounter. Testosterone fogs the air, alongside diesel fumes and the aroma of kebabs darkening over glowing coals. If you are a guest of a Pathan, it is his duty to protect and provide for you:and sudden acts of generosity can cut through the atmosphere of suspicion. As I looked longingly at a stall selling figs and nuts, the owner thrust a heap of samples into my hand. Looking for a chaddar stall,we passed a spice bazaar,and another where all the stalls sold pots and pans.

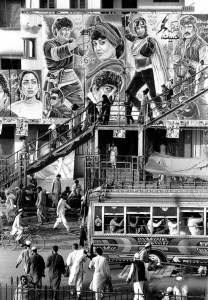

The most famous bazaar of the Old City is the romantically named Qissa Khwani, or Storytellers’Bazaar.Most of the teashops, or khawe-khanas,where travellers once told tall tales,have gone,replaced by tatty luggage stores.But behind the lurid signage and thick bunches of telephone and electric wires, there are finely worked wooden balconies, and the shape of the bazaar is still as laid out by an Italian mercenary general for the Sikh kings before the British came in 1849. Itinerant carpet sellers wander among the stalls, their wares slung across their shoulders in the same way as so many of the Pathans sling their rifles, once they are beyond the gun ban now enforced within the city limits. Beyond pots-and-pans alley we found an open shop on a corner, shawls piled up in shades of brown and grey.The smell of lanolin filled the stall, the woollen mounds rising up to the ceiling, lit by naked bulbs.The grey-bearded owner adjusted his cap as we entered, and his younger assistant looked up at us from where they sat barefoot and cross-legged on the floor.A boy of about 12 sat guard on a chair outside the store. As we unfolded the long,wide shawls, the assistant took a series of calls on his mobile, pausing only to order the boy around. The owner, the assistant and the boy did not smile during inspection or purchase. It was only when I tried to wrap one of the shawls around my shoulders, Pathan-style, that they laughed. We did too,and the temperature changed.

As we left the Old City, driving past the massive Bala Hissar fort built by the Moghul emperor Babur, then the calm gardened precincts of the Britishbuilt cantonment, and finally onto the road that heads out to the Khyber Pass, Peshawar’s history felt very much alive. Unfortunately the visual evidence of Peshawar’s romantic past is under threat. Heroin money, remittances from the Gulf, and the rapacious ‘frontier timber mafia’ are rapidly transforming the face of the city. New shopping plazas go up every month.The fort, the cantonment and the biggestVictorian Gothic buildings, like the Peshawar museum,are probably safe from demolition.But the smaller structures that give evidence of Peshawar’s past are not. City gates, Mughal gardens, the old Afghan Jewish serai,ancient papal trees and the oldest British cemetery,have all disappeared in recent years.Virtually the only greenery left in a city once famous for its flowers and gardens is in the cantonment area, and even that is under threat.Deans, the city’s famous colonial-era hotel,a notorious haunt of spies and journalists during the Soviet-Afghan war,was knocked down almost overnight in 2006 to be replaced with yet another shopping mall. This provoked a stalwart group of Peshawaris to form preservation organisations like the Frontier Heritage Association. It has saved the Mohfiz Khana, a 150-year-old court building still piled with yellowing property deeds,and the trees along the cantonment’s wide mall.But preservation laws go generally unenforced,and anyone who wants to see Peshawar’s remaining Raj and pre-Raj monuments should go soon.

Increasingly Peshawar looks,smells and sounds like any other noisy polluted South Asian city:low-slung concrete blocks,luridly coloured,hand-painted hoardings,and dust that turns into mud after the rains. But Peshawar does feel different. Somehow you always know that you are at the end of the line.Peshawar is the terminus of the ancient Great Trunk Road that runs all the way from Calcutta, the final stop on the main branch of Pakistan’s railway, and the last city under the control of a functioning state for hundreds of miles.There is a palpable sense that this is the furthest reach of settled civilisation and the gateway to a genuinely wild west.The comforts of Peshawar may not be much,and there may be the occasional bomb or riot, but compared to what lies beyond it represents order, safety,even luxury. This has been so for centuries – the name Peshawar means ‘Frontier Town’ in Persian – and will be so for as long as the tribes along the Afghan border remain armed and unconquered.

Top destinations in Peshawar

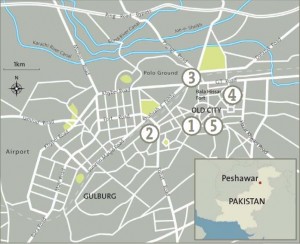

1] Qissa Khawani Bazzaar Fruit stalls provide vibrant colour in this busy market. There are also aromas of bread, kebabs and tikkas sizzling on hot coals.

2] Peshawar Museum The imposing building displays collections of Gandhara sculptures,images of tribal

life, coins,manuscripts, copies of the Koran,weapons, dresses and jewellery.

3] Bala Hissar This mighty fort, built by Babur,the first Moghul ruler, is positioned on the approach to Peshawar from Rawalpindi and the Khyber Pass. Foreboding battlements and ramparts kept angry hordes at bay.

4] Mahabat Khan´s Mosque A small entrance in the middle of Ander Sher Bazaar leads to this beautiful Mughal structure built in the 1670s.Two minarets look over an open courtyard with an ablution pond.

5] Chowk Yadgar Old Peshawar’s central square is a great place to meet friends and regain your bearings after wandering the small streets. The central monument commemorates the 1965 war between India and Pakistan.

Khan Club Hotel Located in the oldest part of the city and dating back 200 years, the recently refurbished Khan Club is luxurious and well loved for its food.

Greens’s Hotel A centrally located hotel that goes easy on the wallet. Drinking tea in the enormousatrium, where vine s dangle down the walls, is a nice way to end a hard day exploring the city.

Rose Hotel Situated at the Khyber Bazaar, this is one of the best and most luxurious hotels in Peshawar, with well trained staff, good food,as well as conference and meeting room facilities.

Pearl Continental Renowned for its service, this six-story hotel is close to the famous Bala Hissar Fort.