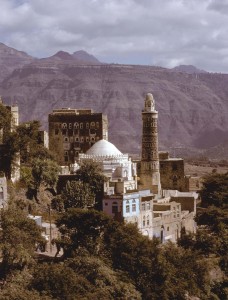

Yemen Cityscape of San’a. There among that unique and dazzling architecture was the house where I had lived when I first arrived in Yemen in 1986. I’m pleased to say it looks in much better condition now, with the whitewashed patterns neatly done and the external plumbing features tidied away. The 1980s were the city’s Richard Rogers period: electricity and water had arrived (usually fed along the narrow lanes somewhere above ground, then clambering up the walls, ducking through tiny windows, then out again and across to a neighbour’s). The city was sporting its modernity on top of the old: who cared if all these pipes and cables were meant to be urban underwear? That first house had water problems, and the plumber arrived with a cigarette in his mouth, a large wad of qat in his cheek, and a wrench in his hand. ‘Is this the faulty tap?’ I nodded. He took a swing at it with the wrench and knocked the thing clean off. The rooftop tank (shaped like a Scud missile to impress American spy satellites, said the neighbours) was full, and so a jet of water shot out of the gaping pipe and hit the far wall. The bathroom filled with drifting spray and six inch deep puddles. The plumber worked on, his cigarette miraculously unextinguished. Until that moment – a few weeks into my time – I had been pretty much obsessed with the look of Yemen. There was an undeniable snootiness to some of my attitudes.

Yemen Cityscape of San’a. There among that unique and dazzling architecture was the house where I had lived when I first arrived in Yemen in 1986. I’m pleased to say it looks in much better condition now, with the whitewashed patterns neatly done and the external plumbing features tidied away. The 1980s were the city’s Richard Rogers period: electricity and water had arrived (usually fed along the narrow lanes somewhere above ground, then clambering up the walls, ducking through tiny windows, then out again and across to a neighbour’s). The city was sporting its modernity on top of the old: who cared if all these pipes and cables were meant to be urban underwear? That first house had water problems, and the plumber arrived with a cigarette in his mouth, a large wad of qat in his cheek, and a wrench in his hand. ‘Is this the faulty tap?’ I nodded. He took a swing at it with the wrench and knocked the thing clean off. The rooftop tank (shaped like a Scud missile to impress American spy satellites, said the neighbours) was full, and so a jet of water shot out of the gaping pipe and hit the far wall. The bathroom filled with drifting spray and six inch deep puddles. The plumber worked on, his cigarette miraculously unextinguished. Until that moment – a few weeks into my time – I had been pretty much obsessed with the look of Yemen. There was an undeniable snootiness to some of my attitudes.

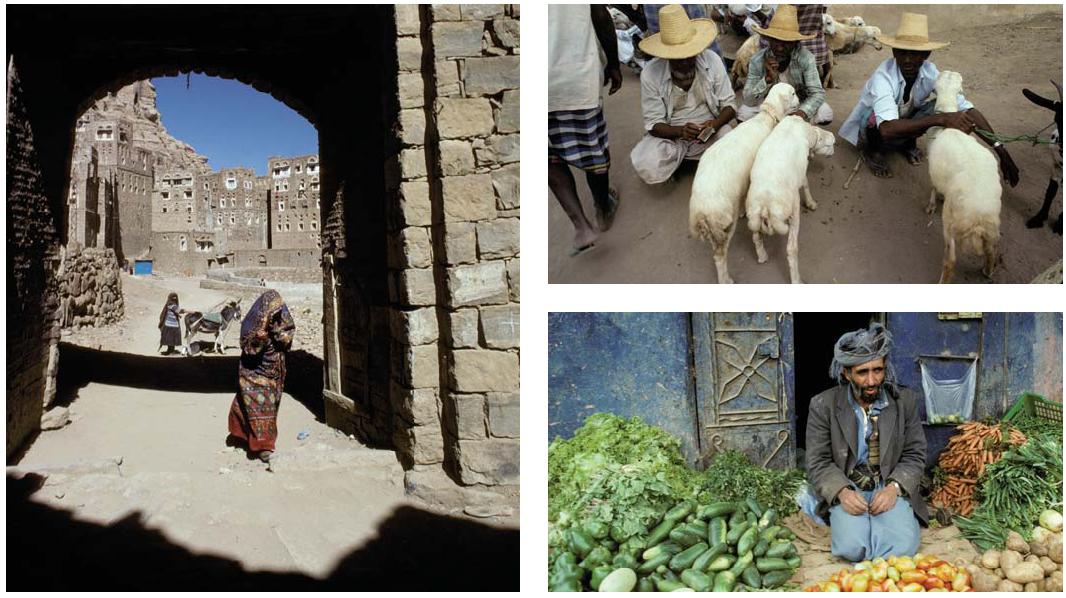

I expressed annoyance at mountains of litter; I tutted over those knotted cables dangling in the streets and the scaffolding of pipework that propped itself on every house. I wanted a Yemen that might have existed 20 years before. I certainly did not want the road to be a hammered tin skin of soft drinks cans, as it was in many places. But the plumber opened my eyes. Before the tank was quite empty he had replaced the faulty tap, changed a length of pipe and mended the ballcock. The entire operation took a few minutes and the cigarette never left his lips. We were both drenched. Then he offered me some qat leaves and a cigarette. We retired to the mafraj, the cushioned living room, with wonderful views of the city. I produced a bag of qat and dropped a handful of leaves in his lap. The question of payment was airily waved away. Then we sat as the light took on that marvellous glow of late evening, and he began to recite poetry.

I expressed annoyance at mountains of litter; I tutted over those knotted cables dangling in the streets and the scaffolding of pipework that propped itself on every house. I wanted a Yemen that might have existed 20 years before. I certainly did not want the road to be a hammered tin skin of soft drinks cans, as it was in many places. But the plumber opened my eyes. Before the tank was quite empty he had replaced the faulty tap, changed a length of pipe and mended the ballcock. The entire operation took a few minutes and the cigarette never left his lips. We were both drenched. Then he offered me some qat leaves and a cigarette. We retired to the mafraj, the cushioned living room, with wonderful views of the city. I produced a bag of qat and dropped a handful of leaves in his lap. The question of payment was airily waved away. Then we sat as the light took on that marvellous glow of late evening, and he began to recite poetry.

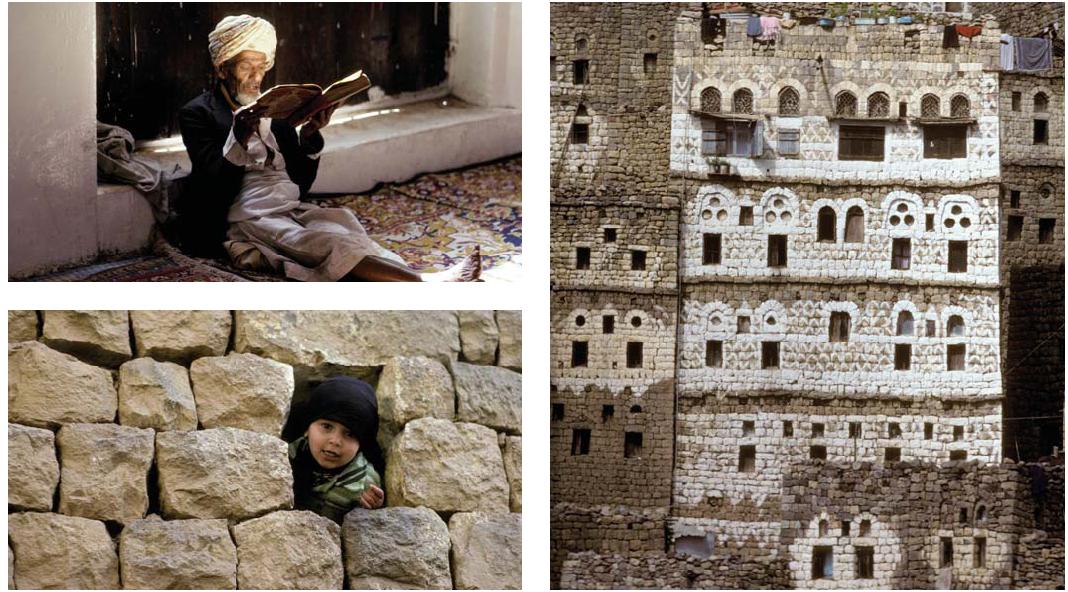

I listened, without comprehending as my Arabic was in a rudimentary state, but it sounded magnificent. When he finished, I gleaned that it was his own composition about the glories of San’a. I was impressed: by the sheer chutzpah of his plumbing performance, by his contempt for other plumbers’ rules, by the superb adaptability of a man whose entire tool kit consisted of one rusty wrench and a cigarette lighter, and most of all by his renaissanceman abilities with language. I learned a little about the way Yemen worked that day, and I looked with fresh eyes on the wayward pipework and all other forms of anarchic organisation. Other, similar lessons began to occur. There was the taxi driver who mended his engine with his janbia – the ceremonial dagger that Yemenis traditionally carry. There was another who smiled when my Landcruiser knocked his car door clean off. ‘Not a problem,’ he proclaimed when I apologised profusely. ‘This is Yemen.’ Out in the mountains I was met usually with hospitality, sometimes with stones, occasionally with total bafflement. ‘Are you a Korean?’ asked one woman.

I listened, without comprehending as my Arabic was in a rudimentary state, but it sounded magnificent. When he finished, I gleaned that it was his own composition about the glories of San’a. I was impressed: by the sheer chutzpah of his plumbing performance, by his contempt for other plumbers’ rules, by the superb adaptability of a man whose entire tool kit consisted of one rusty wrench and a cigarette lighter, and most of all by his renaissanceman abilities with language. I learned a little about the way Yemen worked that day, and I looked with fresh eyes on the wayward pipework and all other forms of anarchic organisation. Other, similar lessons began to occur. There was the taxi driver who mended his engine with his janbia – the ceremonial dagger that Yemenis traditionally carry. There was another who smiled when my Landcruiser knocked his car door clean off. ‘Not a problem,’ he proclaimed when I apologised profusely. ‘This is Yemen.’ Out in the mountains I was met usually with hospitality, sometimes with stones, occasionally with total bafflement. ‘Are you a Korean?’ asked one woman.

And when I said not, she became even more puzzled. ‘So what are you then?’ Over the years that I’ve spent either living in or visiting Yemen, the country has moved on a lot. People are better travelled and more worldly: satellite television has seen to that. Old San’a has been extensively improved: lanes are paved with stone and the pipework is generally straighter. Outside the capital, roads are much improved. But the spirit remains the same. On my most recent visit, I chewed qat in the back of a shared taxi heading for Aden. This is the quintessential Yemeni experience. The mountains roll by and the passengers, Chaucer-like, share stories. One man was an off-duty tour guide and his tale was a truly memorable one. His family lived in the town of Ta’iz, he told us, but long ago had come from al-Jawf, a somewhat volatile area in the north-east of the country. During the late 1990s, when kidnappings were common, he had been taken prisoner along with a party of French tourists. They were all taken to a village in the Jawf where, a couple of qat sessions later, the driver discovered that this was where his grand-father had originally come from. Evidently he had been kidnapped by his own family. The villagers had no intention of harming their ‘guests’. In fact they treated them like royalty. All they required was that the government build the road and school they had been promised. The tourists, rather warming to their hosts, agreed. After three weeks, Stockholm syndrome kicked in and the tourists sent out a demand for the road and school. When a deal was reached, the village tried to release the hostages, but they refused to leave. The deal was not good enough, they said. Eventually the government ‘rescued’ the tourists against their will. The driver thought the whole episode hilarious. He had gone back to visit subsequently, and was hoping the country cousins might pay a visit to Ta’iz. He shrugged, ‘This country is not like any other! What can anyone say ? This is Yemen.’

And when I said not, she became even more puzzled. ‘So what are you then?’ Over the years that I’ve spent either living in or visiting Yemen, the country has moved on a lot. People are better travelled and more worldly: satellite television has seen to that. Old San’a has been extensively improved: lanes are paved with stone and the pipework is generally straighter. Outside the capital, roads are much improved. But the spirit remains the same. On my most recent visit, I chewed qat in the back of a shared taxi heading for Aden. This is the quintessential Yemeni experience. The mountains roll by and the passengers, Chaucer-like, share stories. One man was an off-duty tour guide and his tale was a truly memorable one. His family lived in the town of Ta’iz, he told us, but long ago had come from al-Jawf, a somewhat volatile area in the north-east of the country. During the late 1990s, when kidnappings were common, he had been taken prisoner along with a party of French tourists. They were all taken to a village in the Jawf where, a couple of qat sessions later, the driver discovered that this was where his grand-father had originally come from. Evidently he had been kidnapped by his own family. The villagers had no intention of harming their ‘guests’. In fact they treated them like royalty. All they required was that the government build the road and school they had been promised. The tourists, rather warming to their hosts, agreed. After three weeks, Stockholm syndrome kicked in and the tourists sent out a demand for the road and school. When a deal was reached, the village tried to release the hostages, but they refused to leave. The deal was not good enough, they said. Eventually the government ‘rescued’ the tourists against their will. The driver thought the whole episode hilarious. He had gone back to visit subsequently, and was hoping the country cousins might pay a visit to Ta’iz. He shrugged, ‘This country is not like any other! What can anyone say ? This is Yemen.’